- Home

- About us

- community

- Activities

- What’s On?

- Performed Activities

- Concerts

- Exhibitions

- Exposición de arte de IA Pioneros y expansión del arte de IA-Piano

- Exposición virtual Juan O´Gorman vestigios de arquitectura escolar

- Exposición Arqueologías. Artista: Eloy Tarcisio

- Tierra incógnita

- Ofrenda Casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

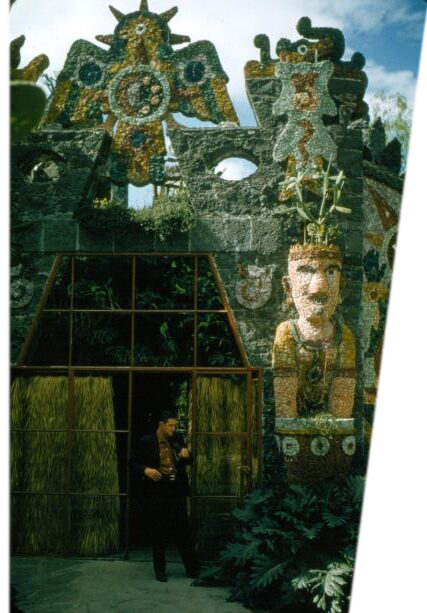

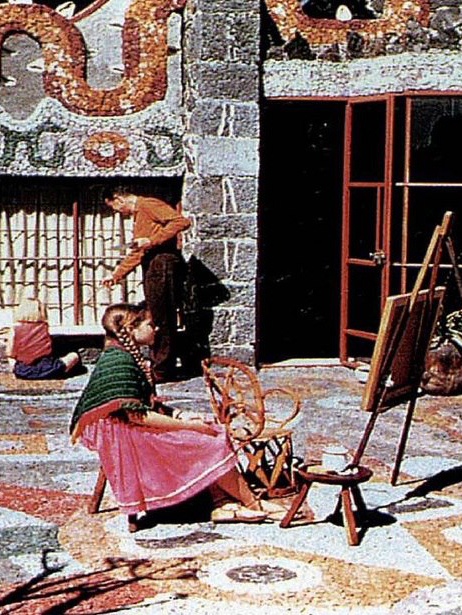

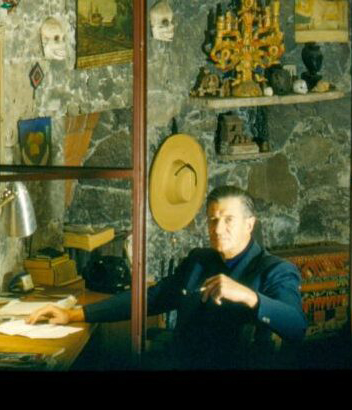

- Juan O’Gorman y su casa cueva

- Arquitectura rebelde

- Del trazo a la materia

- Conferences

- XL Simposium Internacional

- Conferencia La escultura de Angela Gurria

- Charla Explorando el legado de Juan O´Gorman

- Caja de tiempo y sonido. La casa estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Las casas de la Ciudad de México

- Charla Pensar la arquitectura desde los afectos y la memoria

- Charla Espacio Nancarrow O´Gorman sobre las potencialidades sociales del arte y la labor

- Charla ¿Qué sí es y qué no es arte?

- Juan O´Gorman. Preguntas y respuestas con Adriana Sandoval.

- Entrevista a Mtra. Adriana Sandoval

- Charla Arte, subversión y resistencia

- Charla Escultura y Arquitectura

- Juan O´Gorman. Arquitectura, memoria y acción

- Primer Congreso de Pensamiento Crítico y Muralismo

- La memoria de las piedras

- Workshops

- Public Space

- Distinctions

- Precedents

- Link-up

- Inter-institutional Link

- Social Linkage

- Rifa de nacimiento

- Presentación del libro Revolución y Diseño

- Experiencia culinaria desarrollada por Santo Miguelito

- Experiencia culinaria

- Recaudación para el día del niño y la niña

- Argelia Matus. Contar el polvo de la tierra

- Identidad y comunidad en la gráfica

- Introducción a la técnica del stencil

- Maricarmen Graue Talk

- Talk about artistic appreciation in public space

- Press

- Press kit

- Archive

- In Praise of Caves

- Artículos Exposición Centro Cultural Jaime Torres

- Artículos sobre Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Casa de la Primera Imprenta en América UAM

- Artículos exposición Tierra incógnita

- Artículos exposición Bellas Artes

- Artículos sobre Juan O’Gorman

- Artículos sobre casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Universidad Iberoamricana

- Amistades Estructurales

- Special Programs

Menu

- Home

- About us

- community

- Activities

- What’s On?

- Performed Activities

- Concerts

- Exhibitions

- Exposición de arte de IA Pioneros y expansión del arte de IA-Piano

- Exposición virtual Juan O´Gorman vestigios de arquitectura escolar

- Exposición Arqueologías. Artista: Eloy Tarcisio

- Tierra incógnita

- Ofrenda Casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Juan O’Gorman y su casa cueva

- Arquitectura rebelde

- Del trazo a la materia

- Conferences

- XL Simposium Internacional

- Conferencia La escultura de Angela Gurria

- Charla Explorando el legado de Juan O´Gorman

- Caja de tiempo y sonido. La casa estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Las casas de la Ciudad de México

- Charla Pensar la arquitectura desde los afectos y la memoria

- Charla Espacio Nancarrow O´Gorman sobre las potencialidades sociales del arte y la labor

- Charla ¿Qué sí es y qué no es arte?

- Juan O´Gorman. Preguntas y respuestas con Adriana Sandoval.

- Entrevista a Mtra. Adriana Sandoval

- Charla Arte, subversión y resistencia

- Charla Escultura y Arquitectura

- Juan O´Gorman. Arquitectura, memoria y acción

- Primer Congreso de Pensamiento Crítico y Muralismo

- La memoria de las piedras

- Workshops

- Public Space

- Distinctions

- Precedents

- Link-up

- Inter-institutional Link

- Social Linkage

- Rifa de nacimiento

- Presentación del libro Revolución y Diseño

- Experiencia culinaria desarrollada por Santo Miguelito

- Experiencia culinaria

- Recaudación para el día del niño y la niña

- Argelia Matus. Contar el polvo de la tierra

- Identidad y comunidad en la gráfica

- Introducción a la técnica del stencil

- Maricarmen Graue Talk

- Talk about artistic appreciation in public space

- Press

- Press kit

- Archive

- In Praise of Caves

- Artículos Exposición Centro Cultural Jaime Torres

- Artículos sobre Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Casa de la Primera Imprenta en América UAM

- Artículos exposición Tierra incógnita

- Artículos exposición Bellas Artes

- Artículos sobre Juan O’Gorman

- Artículos sobre casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Universidad Iberoamricana

- Amistades Estructurales

- Special Programs

- Home

- About us

- community

- Activities

- What’s On?

- Performed Activities

- Concerts

- Exhibitions

- Exposición de arte de IA Pioneros y expansión del arte de IA-Piano

- Exposición virtual Juan O´Gorman vestigios de arquitectura escolar

- Exposición Arqueologías. Artista: Eloy Tarcisio

- Tierra incógnita

- Ofrenda Casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Juan O’Gorman y su casa cueva

- Arquitectura rebelde

- Del trazo a la materia

- Conferences

- XL Simposium Internacional

- Conferencia La escultura de Angela Gurria

- Charla Explorando el legado de Juan O´Gorman

- Caja de tiempo y sonido. La casa estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Las casas de la Ciudad de México

- Charla Pensar la arquitectura desde los afectos y la memoria

- Charla Espacio Nancarrow O´Gorman sobre las potencialidades sociales del arte y la labor

- Charla ¿Qué sí es y qué no es arte?

- Juan O´Gorman. Preguntas y respuestas con Adriana Sandoval.

- Entrevista a Mtra. Adriana Sandoval

- Charla Arte, subversión y resistencia

- Charla Escultura y Arquitectura

- Juan O´Gorman. Arquitectura, memoria y acción

- Primer Congreso de Pensamiento Crítico y Muralismo

- La memoria de las piedras

- Workshops

- Public Space

- Distinctions

- Precedents

- Link-up

- Inter-institutional Link

- Social Linkage

- Rifa de nacimiento

- Presentación del libro Revolución y Diseño

- Experiencia culinaria desarrollada por Santo Miguelito

- Experiencia culinaria

- Recaudación para el día del niño y la niña

- Argelia Matus. Contar el polvo de la tierra

- Identidad y comunidad en la gráfica

- Introducción a la técnica del stencil

- Maricarmen Graue Talk

- Talk about artistic appreciation in public space

- Press

- Press kit

- Archive

- In Praise of Caves

- Artículos Exposición Centro Cultural Jaime Torres

- Artículos sobre Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Casa de la Primera Imprenta en América UAM

- Artículos exposición Tierra incógnita

- Artículos exposición Bellas Artes

- Artículos sobre Juan O’Gorman

- Artículos sobre casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Universidad Iberoamricana

- Amistades Estructurales

- Special Programs

Menu

- Home

- About us

- community

- Activities

- What’s On?

- Performed Activities

- Concerts

- Exhibitions

- Exposición de arte de IA Pioneros y expansión del arte de IA-Piano

- Exposición virtual Juan O´Gorman vestigios de arquitectura escolar

- Exposición Arqueologías. Artista: Eloy Tarcisio

- Tierra incógnita

- Ofrenda Casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Juan O’Gorman y su casa cueva

- Arquitectura rebelde

- Del trazo a la materia

- Conferences

- XL Simposium Internacional

- Conferencia La escultura de Angela Gurria

- Charla Explorando el legado de Juan O´Gorman

- Caja de tiempo y sonido. La casa estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Las casas de la Ciudad de México

- Charla Pensar la arquitectura desde los afectos y la memoria

- Charla Espacio Nancarrow O´Gorman sobre las potencialidades sociales del arte y la labor

- Charla ¿Qué sí es y qué no es arte?

- Juan O´Gorman. Preguntas y respuestas con Adriana Sandoval.

- Entrevista a Mtra. Adriana Sandoval

- Charla Arte, subversión y resistencia

- Charla Escultura y Arquitectura

- Juan O´Gorman. Arquitectura, memoria y acción

- Primer Congreso de Pensamiento Crítico y Muralismo

- La memoria de las piedras

- Workshops

- Public Space

- Distinctions

- Precedents

- Link-up

- Inter-institutional Link

- Social Linkage

- Rifa de nacimiento

- Presentación del libro Revolución y Diseño

- Experiencia culinaria desarrollada por Santo Miguelito

- Experiencia culinaria

- Recaudación para el día del niño y la niña

- Argelia Matus. Contar el polvo de la tierra

- Identidad y comunidad en la gráfica

- Introducción a la técnica del stencil

- Maricarmen Graue Talk

- Talk about artistic appreciation in public space

- Press

- Press kit

- Archive

- In Praise of Caves

- Artículos Exposición Centro Cultural Jaime Torres

- Artículos sobre Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Casa de la Primera Imprenta en América UAM

- Artículos exposición Tierra incógnita

- Artículos exposición Bellas Artes

- Artículos sobre Juan O’Gorman

- Artículos sobre casa-estudio Conlon Nancarrow

- Artículos exposición Universidad Iberoamricana

- Amistades Estructurales

- Special Programs